What is the source of our imagination? Where do the images or representations of our imaginations come from? Are we entirely autonomous and self-governed in terms of what we (can/not) imagine? Is it perhaps a unique talent that some are born with while others are considered ‘less creative’? Or is imagination a skill that can be trained and encouraged or neglected and thwarted? What is the role of society and culture in shaping our imaginations? Is there collective imagination? For example – a ‘nation’? What enables and motivates people to imagine differently? Is the possibility of exercising one’s imagination available to everyone equally, or are some more privileged to imagine than others?

These were the questions I asked at the end of my article on the Role of Imagination: Middle Ages and Enlightenment. In it, I looked at the history of the development of the idea of imagination – from the Middle Ages in the thought of Thomas Aquinas to the Enlightenment in the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. I finished that journey through history with the questions that open this post. They bring us out of the metaphysical way of thinking about the role of imagination and into our modern times – a more socially situated, experience-based approach that gained philosophical ground in the 20th and 21st centuries. They lead us to the idea of the social imaginary. Let us explore this idea.

Social Imaginary

Before I delve into the meaning of this concept, a brief detour. As mentioned at the very end of the article on the history of imagination in medieval and Enlightenment philosophy, contemporary philosopher and author Richard Kearney makes the following thought-provoking statement:

We might go so far as to say that genocides and atrocities presuppose a radical failure of narrative imagination.

Richard Kearney (“On Stories”, 2002, p.138)

Kearney has made imagination one of the central themes of his life’s work. When he refers to narrative imagination, he builds on one of his mentors’ ideas – Paul Ricoeur and his concepts of narrative identity and hospitality, both of which accord imagination a critical role. Both thinkers are interested in imagination not merely in metaphysically detached terms but in the context of its influence on our practical understanding – our ethical and political judgments and evaluative interpretations. Therefore, Kearney’s provocative statement quoted above follows Ricoeur’s sentiment expressed roughly ten years earlier (back then – with a focus on Europe) when he claimed that it was “no extravagance to formulate the problem of the future of Europe in terms of imagination.” (Ricoeur, “Reflections on a new ethos for Europe”, p. 3)

And now, back from this short detour to our main question – what is social imaginary?

The thinker who introduced this idea was another mentor of Kearney: philosopher Charles Taylor. He developed his ideas on the social imaginary by drawing on the work of various other thinkers, especially – Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983). Taylor described the concept of social imaginary in the book Modern Social Imaginaries:

“What I’m trying to get at with this term is something much broader and deeper than the intellectual schemes people may entertain when they think about social reality in a disengaged mode. I am thinking rather of the ways in which people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations.”

Taylor (2004, ch.2)

Taylor summarizes his choice of the word ‘imaginary’ in the following three points: “I adopt the term imaginary (i) because my focus is on the way ordinary people “imagine” their social surroundings, and this is often not expressed in theoretical terms, but is carried in images, stories, and legends. It is also the case that (ii) theory is often the possession of a small minority, whereas what is interesting in the social imaginary is that it is shared by large groups of people, if not the whole society. Which leads to a third difference: (iii) the social imaginary is that common understanding that makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy.” (2004, ch.2)

We could come up with some examples of social imaginary: socio-cultural norms and mores of a respective society, what we usually refer to as ‘common sense’ understanding and knowledge (such as that chairs are for sitting on). They are all the ways of thinking about how and what we are and should be and do – usually without realising that we think that. For this reason, Taylor writes that social imaginary is broader and deeper than any social theory could be. A theory implies intellectual work and (at least an effort of) detachment. However, imagination does not intend to say that these deeply rooted ways of thinking and judging are simple. Taylor notes:

“Our social imaginary at any given time is complex. It incorporates a sense of the normal expectations that we have of one another, the kind of common understanding which enables us to carry out the collective practices that make up our social life. This incorporates some sense of how we all fit together in carrying out the common practice. This understanding is both factual and “normative”; that is, we have a sense of how things usually go, but this is interwoven with an idea of how they ought to go, of what missteps would invalidate the practice.” (2004, ch.2, my emphasis)

Note three essential elements of social imaginary that are inseparably intertwined:

- factual understanding

- normative understanding

- collective practices of the social life

Our social life consists of a great variety of collective practices that we perform individually and together, and which are always informed by our understanding of how things are (‘factual’ understanding) and how they should be (‘normative’ understanding). The separation of factual and normative understanding here is purely analytical. In everyday life, it is just our practical understanding and judgment. The relationship between practice and understanding is not linear. One informs the other. Understanding informs the practice – practice maintains understanding. We tend to notice this underlying dynamic when a crisis happens. Think of the COVID pandemic and the ways in which it reshaped both our practice and understanding of, for instance, how we work and communicate with each other and how we should (and can) work and communicate. I am certain that a careful philosophical investigation of the impact of that pandemic would reveal notable changes in social imaginaries across the globe.

Taylor explains: “The relation between practices and the background understanding behind them is therefore not one-sided. If the understanding makes the practice possible, it is also true that the practice largely carries the understanding. At any given time, we can speak of the “repertory” of collective actions at the disposal of a given sector of society. These are the common actions that they know how to undertake, all the way from the general election, involving the whole society, to knowing how to strike up a polite but uninvolved conversation with a casual group in the reception hall.” (2004, ch. 2)

This shows one more reason to talk of social imaginary instead of theory. Taylor uses the word ‘background’ in the above quote. Social imaginary is like a lived ‘background’ without clearly defined borders. This background makes all the various features of our lives appear to us with the sense they have. Think of how we perceive things in the world – it is always against some background, in some sort of ‘context’, which informs the way the perceived thing presents itself to us. Because of this background being a “largely unstructured and inarticulate understanding of our whole situation” (Taylor, 2004, ch.2), it makes sense to speak of a social imaginary rather than a theory.

Taylor offers a useful analogy to show that the understanding-practice dynamic of social imaginary goes both beyond any immediate background of my present situation and deeper than the theoretical framework of a detached observer: “The understanding expressed in practice stands to social theory the way that my ability to get around a familiar environment stands to a (literal) map of this area. I am able to orient myself without ever having adopted the standpoint of overview that the map offers me.” (2004, ch. 2) This is not to downplay the value of theories or maps. Taylor’s point is to illustrate that imagination is a more helpful concept in trying to understand our lived social experiences. Moreover, any work of theory building presumes my already existing background practical understanding, which would allow me to engage with a particular aspect of life as an observer. I cannot draw a map if I have not yet gained the skill of orienting myself in space.

It would be interesting to bring Taylor’s thoughts on social imaginary into conversation with Miranda Fricker’s framework of epistemic injustice. This would raise questions about ‘whose‘ understanding is the ‘common’ understanding that informs ‘common’ practices? For whom is the ‘widely shared’ sense of legitimacy ensured? For example, how do members of marginalised groups contribute to the ‘common’ understanding and collective practices that maintain a social life? In what ways might they be structurally prevented from contributing to the social imaginary, thereby revealing it as a socio-politically dominant collective imaginary? These are questions for another article. For now, I leave you with this short statement Taylor makes, which, in my view, nicely summarizes the idea of the social imaginary in contrast to a social theory:

“The social imaginary is not a set of ideas; rather, it is what enables, through making sense of, the practices of a society.”

Charles Taylor (“Modern Social Imaginaries”, 2004, p.2)

keep exploring!

P.S. Thank you for visiting the humanfactor.blog! If you enjoyed this post and are interested in more philosophical content, I invite you to explore the blog, comment, like, and subscribe to get notified of new posts.

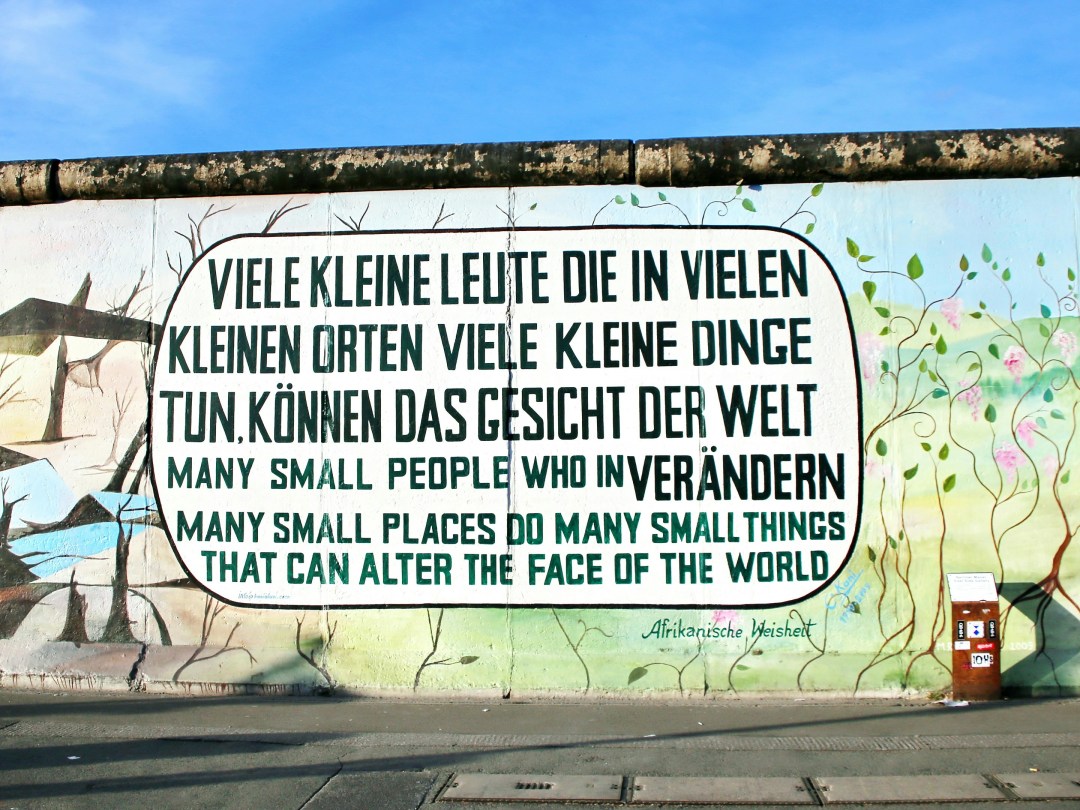

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Mark König on Unsplash. This street art is part of Berlin’s East Side Gallery, painted on the former Berlin Wall.