What is your identity? When someone asks you who you are, what are the first things that come to your mind? Are they your identity? Thinking about our identities is crucial for people, and we do it many times in our lives. It is unsurprising that throughout history, philosophers have engaged with the question of identity and, more precisely – what does the idea of identity actually mean? How can we understand identity as a concept; how should we go about explaining it?

In his book “Derrida: a very short introduction” (2011), Simon Glendinning notes that while everything has an identity, “what makes it what it is… and not another thing”, a deeply intuitive understanding of identity and difference “is in terms of the possession of distinguishing features” and their enduring presence. The way that the enduring presence is ensured constitutes two accounts of identity Glendinning introduces: intrinsic and relational.

Intrinsic identity requires that a thing has certain features that make it what it is and that these features (or enough of them) remain present for the thing to continue being what it is. On this account, the thing’s relation to anything else in the world (and the world’s relation to it) is irrelevant to its identity. This view can also be called essentialist, where your identity consists of features that collectively form your unchanging ‘essence’.

Relational identity incorporates the thing’s relations to other things into its identity. For the thing to remain what it is, it must maintain its specific differences from other things within the “structure of general differentiation” (Glendinning). On this account, identity is ensured and endures in terms of occupying a particular, persisting position in a general structure of relations that must itself last as it is. It is like having your specific place in an unchanging system of coordinates.

According to Glendinning, while Derrida agrees that identity is formed relationally, his counter-conception of identity differs from both presented accounts. It challenges the idea of the persisting presence and givenness of the general system of differences that gives rise to individual relational identities. For him, what I call a system of coordinates is itself subject to change. These systems or structures of relations come to be through differentiation processes. Derrida referred to these processes by a concept of ‘différance’ that he coined and described as “the movement that produces the system of differences” (Glendinning).

It was important for Derrida to challenge the classical metaphysical understanding of meaning (or identity of words, things, phenomena): the ‘one’ true meaning in its ideal purity and permanent presence, transcending all life contingencies. Therefore, if his idea of différance is a movement, it is not a movement toward a definitive meaning, an eternal presence that is merely deferred but can be re-appropriated. In fact, Glendinning argues that différance aims to criticise this “misleading picture of a final moment of restored presence” when we ultimately arrive at the pure meaning of the ‘thing itself’ that the words only secondarily re-present as if trying to bring the ‘thing’ to presence through detours of signs.

Glendinning writes, “It is just this dimension of difference-within-identity that Derrida wants to get into view with his term ‘différance’… Derrida appeals to a second sense belonging to the Latin verb ‘differre‘… namely, ‘the action of putting off’ – deferring”. But what is deferred? The final, ‘pure’ identity of meaning. Thus, it is not because of complete and enduring presence that the meaning is recognised in the present context but because its repeatability in different contexts – forming similar relations with other meanings in diverse contexts – constitutes an integral part of what it is. Quoting Derrida, Glendinning writes, “we provisionally give the name différance to this sameness which is not identical”.

It is by moving through the systems of differences that meanings acquire their discernible identities. Identities take shape through repeatability. Therefore, identity for Derrida is characterised not only by the relation of difference to others but also to oneself, a “self-difference”. In a radically different system of differences, my identity may no longer be repeatable with the same meaning it has now, in the current system of differences. Maybe these are what we call identity crises. But even in less pronounced context changes, repeatability and, thus, identity is performed only through some differentiation. There is sameness but never a complete, perfect, ‘pure’ identity (exactness). Therefore, “every identity has an irreducibly ‘divided identity'” (Glendinning).

The accounts of identity I presented here can be seen as gradual steps from a more specific, isolated level (intrinsic or essentialist) to the meta-structural level, where each step broadens the understanding of identity. Derrida’s idea of différance is the meta-structural level of explaining the general differentiation structures (where individual identities form) as themselves produced by a movement that, as such, has no meaning of its own. This level reveals that the identity-shaping structure has itself a contingent, non-final, constructed identity that can (and does!) change, turning into a new and different system of coordinates.

Why is Derrida’s concept of différance interesting for thinking about our identities? Because it offers a way of understanding identity that recognises the crucial role of relationality and incorporates otherness into the very structure of identity. Thus, our fundamentally relational selves, our identities, become what we experience them to be by moving through and relating to others and ourselves differently in different contexts. We perform our identities.

keep exploring!

P.S. Thank you for visiting me here on the humanfactor.blog! If you enjoyed this post and are interested in more philosophical content, I invite you to explore the blog, leave a comment, like, and subscribe to get notified of new posts.

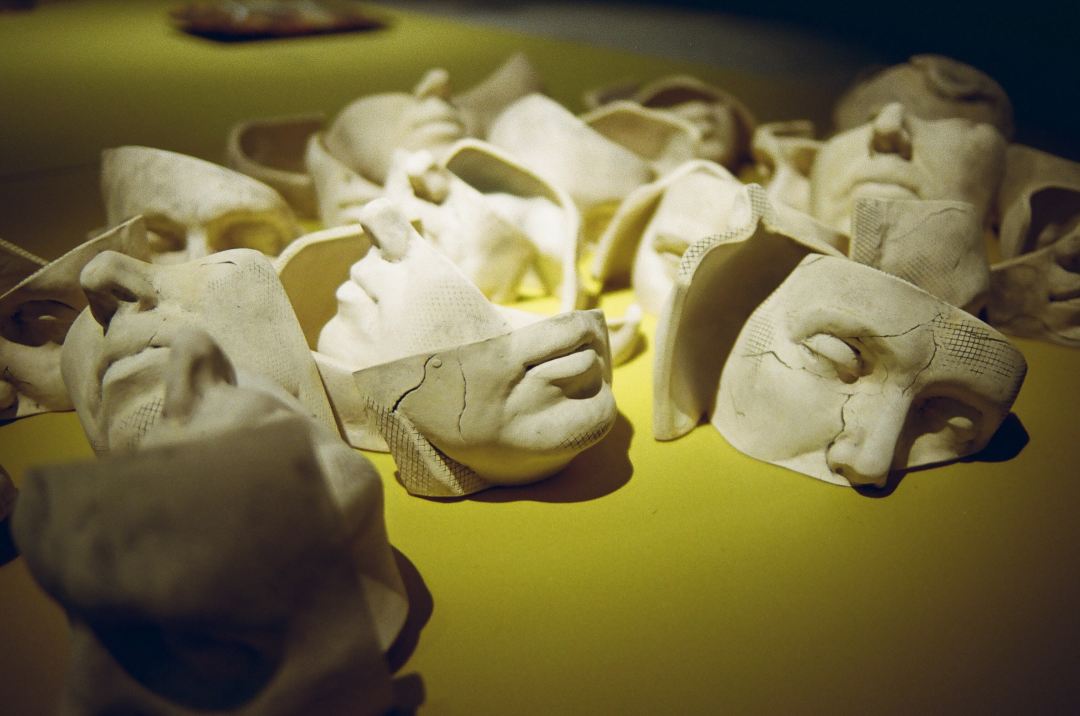

Featured Image credit: Photo by Rach Teo on Unsplash

4 thoughts on “How to Understand Identity”